THÔNG TIN SƯU TẦM

Remdesivir eases covid-19 symptoms in monkeys in 12 hours, small preliminary study shows

Remdesivir, an experimental drug which scientists hope could be used to treat COVID-19, appeared to improve coronavirus symptoms and reduce lung damage in a preliminary study on monkeys.

Scientists infected two groups of six rhesus macaque monkeys with SARS-CoV-2 (the new coronavirus which causes COVID-19 disease) so they developed a lower respiratory tract infection.

12 hours after the animals were infected, and once a day for six days thereafter, the team either gave the animals remdesivir intravenously or a control substance which didn't contain the drug. This dosing schedule mimics what human COVID-19 patients are given in clinical studies, the team said. The team regularly checked the monkeys' symptoms and how much of the virus they were carrying. After seven days they euthanized the animals and performed autopsies.

Compared with the control group, the animals given remdesivir "did not show signs of respiratory disease" and scans showed their lungs contained less substances linked to pneumonia.

"As early as 12hrs after the first treatment was administered," levels of the virus in the animals' lower respiratory system dropped, the team said.

However virus levels weren't reduced in nose, throat, or rectals swabs taken form the animals treated with the drug after 12 hours. After one day and four days, virus levels were lower in throat swabs.

Autopsies revealed the viral load in the lungs of animals given the drug "were significantly lower and there was a clear reduction in damage to the lung tissue," according to the study.

The team concluded: "Therapeutic remdesivir treatment initiated early during infection has a clear clinical benefit in SARS-CoV-2-infected rhesus macaques. These data support early remdesivir treatment initiation in COVID-19 patients to prevent progression to severe pneumonia"

Data from such studies can help with the search for treatments in humans "by ruling out treatments without proven efficacy in vivo [in living organisms]," they said.

But the researchers acknowledged: "due to the acute nature of the disease in rhesus macaques, it is hard to directly translate the timing of treatment used to corresponding disease stages in humans."

Remdesivir was given "close to the peak of virus replication in the lungs as indicated by viral loads" and lower respiratory tests, and "the first effects of treatment on clinical signs and virus replication were observed within 12 hours," the scientists said.

Typically, this type of antiviral becomes less effective against acute viral respiratory tract infections when the start of treatment is delayed, according to the team. "Thus, remdesivir treatment in COVID-19 patients should be initiated as early as possible to achieve the maximum treatment effect."

Scientists at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and remdesivir creator Gilead Sciences worked on the study. The fact some of the authors are affiliated with, employed by and own stocks in Gilead Sciences was reported as a potential conflict of interest.

The study was submitted as a pre-print to the website bioRxiv, meaning it hasn't been through the rigorous peer review process required to publish in scientific journals. Releasing studies this way means scientists can prompt debate on a topic and is particularly useful during a fast-moving situation like a pandemic when it is useful to release and discuss information quickly.

There is currently no specific treatment for COVID-19, the disease which this week hit 2 million known cases, according to Johns Hopkins University. Almost 146,000 people have died of the disease, and more than 550,453 have recovered.

Remdesivir was created with Ebola in mind but had promising results against MERS and SARS. The scientists are among those investigating the potential uses of the drug against COVID-19. Other similar work is being carried out in Europe as well as the U.S. and China. The drug appeared to be safe in humans after it was used compassionately in COVID-19 patients in the U.S., although more research is needed to confirm the results.

On Thursday, early results from a clinical trial carried out in COVID-19 patients by the University of Chicago appeared to have promising results.

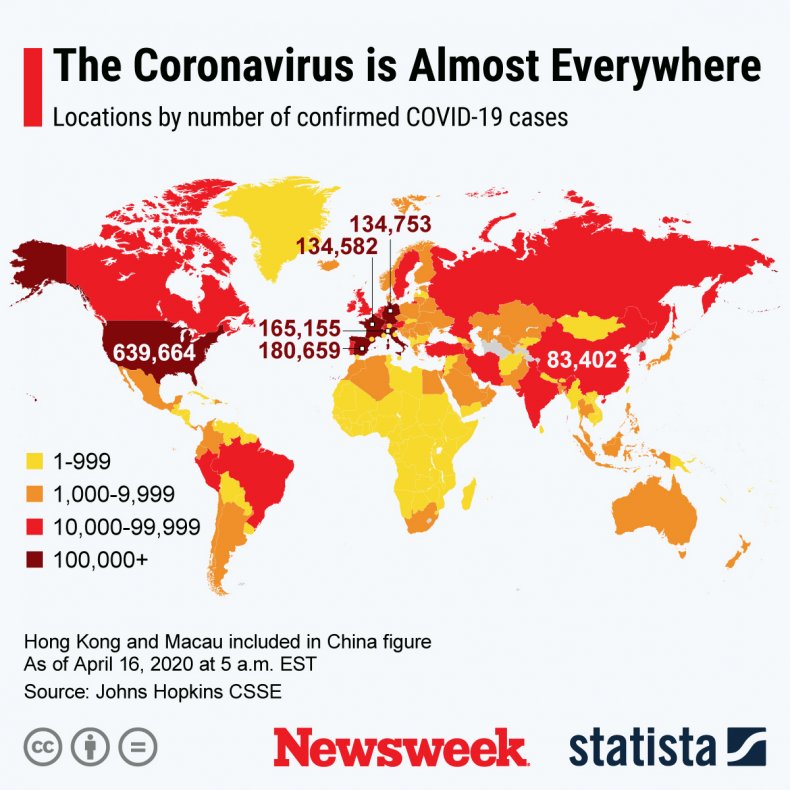

As the Statista map below shows, the coronavirus has reached almost everyone corner of the globe.

A graphic provided by Statista shows the global spread of the new coronavirus as of early April 16. More than 2.1 million people have been afflicted, over 530,000 of whom have recovered and over 140,000 of whom have died.STATISTA

Andrew Preston, reader in microbial pathogenesis at the University of Bath who did not work on the study, told Newsweek the findings offer hope that the drug may be helpful for treating COVID19 "and certainly supports the continuation of a number of clinical trials of remdesivir that are underway."

Preston said: "Importantly, although the drug appeared to reduce the severity of disease, it did not significantly affect shedding of the virus, so if used in patients, even though their symptoms may improve, they should be considered to remain infectious to others and monitored for complete clearance of the virus.

"This suggests that the drug may be a therapy for disease," but can't be used to prevent the virus from spreading, for instance in healthcare workers.

Preston praised the authors for using a range of markers to score how severe disease was, and for measuring both viral load and presence of infectious virus in samples.

The study being conducted in animals presented both strengths and weaknesses, said Preston. An animal model shows more than an analysis of the drug's effects a sample of the virus in a lab.

But Preston said that effects in animals won't necessarily translate to humans. Preston also argued the study's small sample size was another limitation, so extrapolation the results in a larger sample of subjects "needs to be done with caution."

"The rhesus macaques suffer a relatively short lived disease from COVID," Preston continued. "How this translates to the much more prolonged infection course in people is unclear. It suggests that compared to humans who suffer disease, the macaques are innately better at clearing the virus. This may boost the effectiveness of the drug in this model."

In addition, the drug was given to the subjects "very soon" after they were infected.

"It is very likely that this would be a different point in the infection cycle compared to use in humans who will have had the virus for much longer before they display symptoms and become ill enough to seek medical help (and thus therapy). The validity of extrapolating from this study to that scenario in humans is unclear," said Preston.

Despite these limitations, Preston added, the study "provides further motivation for trialling the drug in controlled clinical trials in humans that are underway, and points to careful monitoring of viral shedding from patients in those trials."

Ian Hall, professor of molecular medicine at the University of Nottingham, who also didn't work on the study, told Newsweek: "Current clinical trials of antiviral drugs in patients with COVID19 have generally administered the drug much later in the disease process, by which time significant lung damage has probably already occurred, which could explain why to date the clinical studies on antivirals have failed to show marked beneficial effects."

Hall said if the effects seen in the study translate in humans the biggest problem would be pinpointing when treatment should be started, as symptoms do not usually develop until a few days after exposure to the virus.

"One option would be to treat patients as soon as they develop the first symptoms, but this is likely to be quite a lot longer after exposure than the 12 hour period used in the study reported in this paper," said Hall.

"The approach could, though, be extended to treating close (asymptomatic) contacts of cases, again to commence treatment as early as possible in those at risk of developing severe disease.

"Both of these options would require rapid identification of cases which would require scaled up community diagnostic screening to be in place."

Hall stressed: "It is important not to jump too rapidly to conclusions about new treatment approaches, but these data could certainly be used to help design a formal clinical trial which aimed to treat as early as possible in the disease process."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advice on Using Face Coverings to Slow Spread of COVID-19

- CDC recommends wearing a cloth face covering in public where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain.

- A simple cloth face covering can help slow the spread of the virus by those infected and by those who do not exhibit symptoms.

- Cloth face coverings can be fashioned from household items. Guides are offered by the CDC. (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/diy-cloth-face-coverings.html)

- Cloth face coverings should be washed regularly. A washing machine will suffice.

- Practice safe removal of face coverings by not touching eyes, nose, and mouth, and wash hands immediately after removing the covering.

World Health Organization advice for avoiding spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

Hygiene advice

- Clean hands frequently with soap and water, or alcohol-based hand rub.

- Wash hands after coughing or sneezing; when caring for the sick; before, during and after food preparation; before eating; after using the toilet; when hands are visibly dirty; and after handling animals or waste.

- Maintain at least 1 meter (3 feet) distance from anyone who is coughing or sneezing.

- Avoid touching your hands, nose and mouth. Do not spit in public.

- Cover your mouth and nose with a tissue or bent elbow when coughing or sneezing. Discard the tissue immediately and clean your hands.

Medical advice

- Avoid close contact with others if you have any symptoms.

- Stay at home if you feel unwell, even with mild symptoms such as headache and runny nose, to avoid potential spread of the disease to medical facilities and other people.

- If you develop serious symptoms (fever, cough, difficulty breathing) seek medical care early and contact local health authorities in advance.

- Note any recent contact with others and travel details to provide to authorities who can trace and prevent spread of the disease.

- Stay up to date on COVID-19 developments issued by health authorities and follow their guidance.

Mask and glove usage

- Healthy individuals only need to wear a mask if taking care of a sick person.

- Wear a mask if you are coughing or sneezing.

- Masks are effective when used in combination with frequent hand cleaning.

- Do not touch the mask while wearing it. Clean hands if you touch the mask.

- Learn how to properly put on, remove and dispose of masks. Clean hands after disposing of the mask.

- Do not reuse single-use masks.

- Regularly washing bare hands is more effective against catching COVID-19 than wearing rubber gloves.

- The COVID-19 virus can still be picked up on rubber gloves and transmitted by touching your face.

Source: newsweek.com

Collected by My Nguyen

Tổng giám đốc WHO: Chưa thể loại trừ khả năng Covid-19 rò rỉ...

Người đứng đầu Tổ chức Y tế Thế giới (WHO) ngày 15.7 cho biết vẫn còn quá...

Một tuần đi qua

Vậy là đã qua được một tuần cách ly toàn TP.HCM theo chỉ thị 16

Khổ vì giấy xét nghiệm Covid-19

Ngày 5.7, tại cuộc họp trực tuyến của Ban Chỉ đạo quốc gia phòng, chống...

TP.HCM đề xuất giám sát người cách ly tại nhà bằng thiết bị...

Sở Thông tin và truyền thông TP.HCM vừa có văn bản đề xuất UBND TP.HCM về...

Không 'đóng cửa' nhưng sẽ kiểm soát chặt chẽ người ra vào...

TP.HCM không đóng cửa hay phong tỏa nhưng sẽ kiểm soát chặt chẽ người ra vào...

TP.HCM: Chiến dịch tiêm 836.000 liều vắc xin Covid-19 kết thúc hôm...

Tính đến hết ngày 29.6, TP.HCM đã tiêm trên 805.000 liều vắc xin Covid-19 trong...

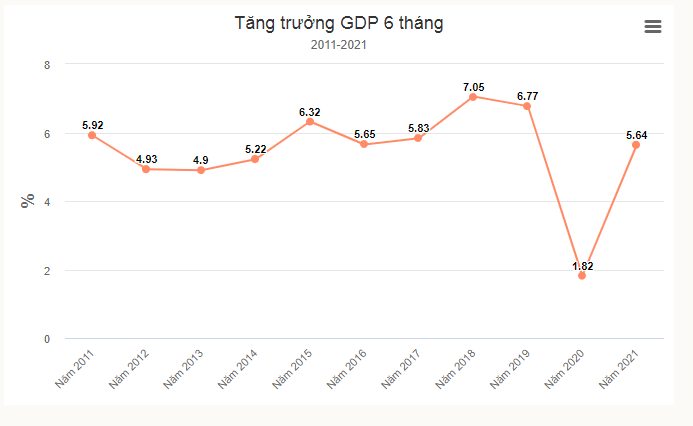

Tại sao 'gánh' dịch, kinh tế vẫn tăng trưởng gấp ba cùng kỳ

Con số GDP 6 tháng tăng 5,64% khiến giới phân tích bất ngờ bởi 2 quý vừa qua,...

Đề nghị Astra Zeneca chuyển cho Việt Nam 10 triệu liều vaccine

Lãnh đạo Chính phủ đề nghị Công ty AstraZeneca tạo mọi điều kiện thuận...

Dịch Covid-19 lan mạnh: Không thi mà xét tốt nghiệp, trường ĐH...

Trước những mong muốn của thí sinh, phụ huynh tổ chức xét tốt nghiệp thay vì...

Dịch vẫn lan nhanh, TP.HCM cần thêm 'thuốc mới'?

Số ca nhiễm tại TP.HCM vẫn tăng lên, ở mức 3 con số mỗi ngày, dù đa số ở...

Trưởng đại diện WHO tại Việt Nam: Người dân TP.HCM hãy tuân...

Theo TS Kidong Park, vai trò của vắc xin trong việc kiểm soát ổ dịch cấp tính còn...

344567942350826358571066.jpg&w=1400&h=520)

522608805487.jpg&w=1400&h=520)